(Or, one writer on Pinterest. You decide.)

(Or, one writer on Pinterest. You decide.)

Hi there, and happy new year. My name is Tamiko, and I just used Pinterest as a writing tool. Still with me? There is, as always, a back story.

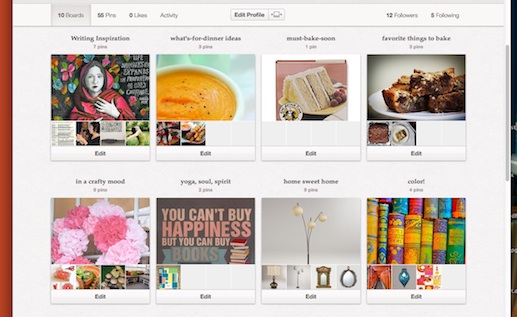

My sister asked me to join Pinterest so I could look at some images that she’s got there. So I rejoined, having lost my original account when the whole deal was still in beta. Friends from Facebook started finding me on Pinterest, and my e-mail started pinging with notifications. I asked my Facebook friends to be patient with me, since I really had no idea about what I was doing there. I asked them for tips on how to work with Pinterest, or if they enjoyed it, or how they liked to use it best.

Some of my Facebook friends described Pinterest as “more addictive than Facebook.” I have also heard some describe it as the least stressful, lowest-maintenance form of social media, because you don’t have to interact with anyone (necessarily) or gain followers or start conversations. The most appealing descriptions made it sound like a place to arrange your own bookmarks, save recipes, or daydream visually. One friend said that she had a vision board there. Those descriptions sounded fun.

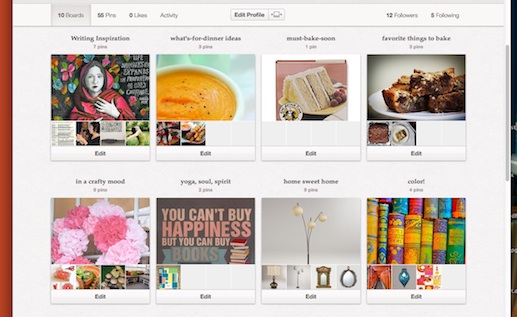

I started “pinning,” or (for the unPinitiated) adding images from sites that I liked, to different “boards,” or subject areas that I created. And oh, it was “luscious,” as another friend put it to shop through different lamps at Cost Plus, and think about the things that I would like to buy for our living room. So pretty! So sparkly! And I liked looking at all the colors together on my boards. I keep wanting to integrate more color into my everyday life and surroundings, and looking at my Pinterest boards does make me happy.

There are aspects of Pinterest that concern me, for my own personality and habits. It can be addictive, another form of fracturing my attention. Already I can feel myself thinking, “Oooooh, I can pin this on my ___ board”—after I update my blog (so 2000s), check my Twitter feed, add books to my Goodreads account and update my Facebook status. I’m not sure I need another thing online to monitor and update. And as a book writer, I need longform attention to read, to write, to think beyond 140 characters or 320 pixels. When you get to the Pinterest home page, you are greeted with more images to click, and when you get to your own home page, there are even more of the same from the people and boards that you are following. It can be overwhelming, unless there is another way to monitor and organize the “boards” that you follow from different people. (There could be. I don’t know yet.)

And so much about Pinterest that I’ve seen (thus far) is about desire: things you’d like to buy, projects you’d like to make, recipes you’d like to test, places you’d like to travel, wall decor for your bathrooms… I should mention that I do have a friend who has created a board of “pins completed,” which sounds like a useful way to keep yourself a bit more accountable instead of adding to an ever-increasing to-do list of pins. I could see myself creating a big list of recipes to cook that I hadn’t cooked yet, and a list of house projects that I hadn’t started (or finished) yet, and feeling pretty terrible.

What worries me the most about Pinterest—again, for myself—is that there is very little space for appreciating what I have. As far as I can tell, the Pinterest gaze looks outward and forward, rather than inward or backward. After a while it felt like looking for my own reflection and having to search for it, over and over again, in the mirrors of other people’s houses. Something like the rabbit hole or funhouse of the Internet search itself. (Alexander Chee, who writes some of the finest online essays I know, has a short one about distractions, writing, and the Internet. One of the best passages:

“The next time you find yourself helplessly in the grip of some internet rabbit hole, take a slight step back, and don’t stop yourself, but ask yourself what it is you are really after. What are the feelings you feel?…[and] whatever it is that is so distracting, would you write more if you wrote about it? Does it want, in other words, to be your subject?”

But one of the Pinterest things I decided to try, on a whim, was to create a “board,” a collection of links and images, for the book I am writing. And, wow. I actually want to keep this board around, and I hope I’ll be able to save it elsewhere somehow, with the other book-related materials. The part of me that keeps jumping ahead to publication says that this Pinterest board could even be part of a marketing tool for the book. Readers might want to know more about certain pieces of the book, and they could look at the board for more information. You can see the entire board here. (I don’t know if you have to be a Pinterest user to see it, so let me know if you can’t see it and you really want to. [Not that any of you need more things to see. I know.])

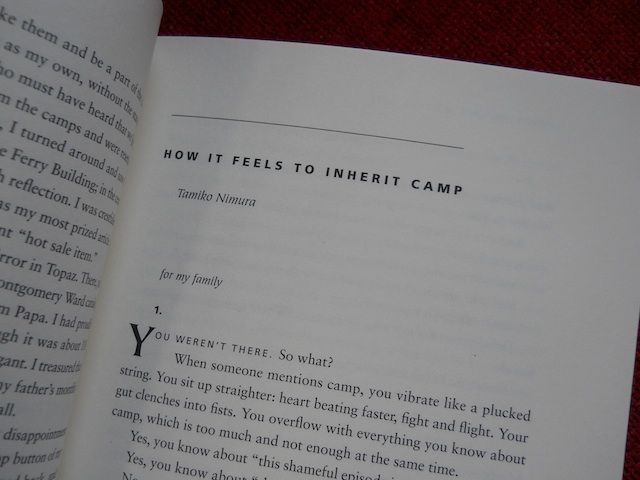

I started with an image of the place in Northern California where my dad and his family ventolin were incarcerated, Tule Lake. I made that the cover image.

Other images followed from sites that I’ve discovered while I’ve been writing and researching the book. An interview with the current poet laureate, Natasha Tretheway, about history’s erasures and memories. A Rumpus article about grief memoirs, another about the genre of memoirs. An Atlantic article about photographers using technology to bring together separated families on the same page, in the same picture. An article on Yoga Journal about a woman who created a yoga workshop specifically for those who are grieving. A national resource center for children and teens who are grieving. A post from my own blog (ooh, I can pin my own content?) to remind me of things that I discovered while writing about grief.

The library where my dad worked for so many years, at Cal State Sacramento.

And an image of my sister’s incredible artwork (which I want to include in the book) of my grandfather’s funeral and the mandala she created over it.

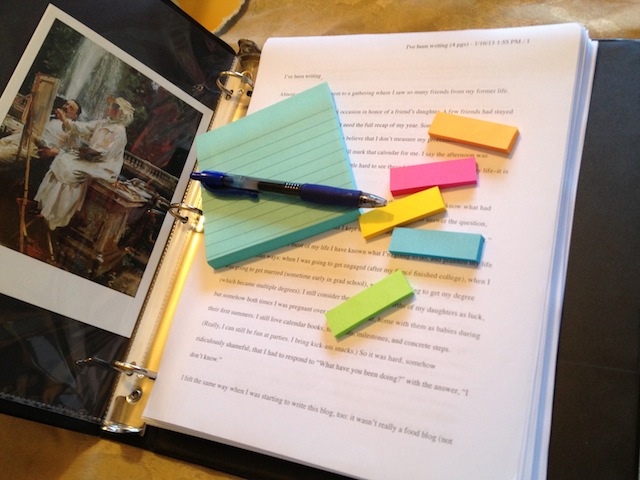

The work of putting the images together was partly frustrating, partly satisfying. Frustrating because as much as I loved working with these images (I usually work in text), there were sites that are important to me and my project. And because there was no image to be “pinned,” I couldn’t add them to my board. There are sites with important paragraphs that I want to read over and over again, and the images were not usable or interesting. I went back through my book journal and tried to find pinnable sites for the board; some worked, others didn’t. It would be nice to have a place for all of them, on a virtual visual cork board like this one.

The satisfaction, though, was the surprise. For example, I don’t know if I ever would have searched for an image of the library where my dad worked. But now, every time I see it, I think about all times I went there, visiting him at work. He used to take me and my sister to every single floor of the library, showing us around, and (yes) showing us off to his co-workers. Just seeing the image made me remember all of that. So it was a good reminder of what the image can do, and how the image lets us viscerally access what text does not.

Captioning each image helped me to do some unexpected short writing assignments for the book. Sometimes I wrote important quotes from the interviews. Sometimes I wrote notes about what the images meant to me. Sometimes I wrote and actually discovered something new about the image for myself. I grabbed an image from the book I’ve been meaning to get, Colors of Confinement, an extraordinary collection of color (color!) photos from camp. As I wrote the caption, I thought about what it means to see camp in full color, when we’re so used to seeing and thinking about camp (at least in the present) in black-and-white, the somewhat distant historical past.

I thought about how seeing camp in color brings camp dramatically into the present, even if only for a while—and that move is something like the move I want people to experience when they read my book.

And perhaps most importantly, my Pinterest board for the book got me out of my writing rut. It inspired me to go back to the book again. Looking at the images together made me click into a looser, freer, right-brain mode of creating. It was a way of playing with the material that I’d like to keep, if I can.

One final surprise, though: it was shocking to see how much that Pinterest book board contrasted with the others. This board has so many black and white images, so many photos of people and paintings. The other boards contain a lot of landscapes and still lifes and objects. To see the book in terms of representative images showed me another way to see its prominent threads. I got to see my book again: it is about loss, and history. It’s about how we use technology and memory in order to recover. And retrieve. And renew. And heal.

A Few Writer Takeaways for Pinterest:

- Use Pinterest as a way to play with the material from your book-in-progress. Create a “board,” or collection of links and images, just for your project. Think about it as a vision board or cork board for the book. Move the images around. See what the collective images on a board tell you about your project. Seeing your text-based book in terms of representative images can unlock some of the material or emotions that “just” writing might not.

- Unless all of your links have interesting, relevant, and usable (“pinnable”) images, Pinterest does not work as well as a place to save all of the links for your book.

- Use the 500-character caption function as a way to do some short writing assignments about each image for your book. (It’s another way to approach Anne Lamott’s famous “one-inch picture frame” assignment in Bird by Bird.)

Have you used online images as a way to spark your writing process? Have you used Pinterest for your own artmaking or writing? Do you have any Pinterest tips? Please leave them in the comments below.

Update, 1/17/13: Laura Harrington has written a similar post about using Pinterest for novelists, here. More useful tips!