And the first questions that may be on your mind: his diary? Isn’t that private? And you’re writing it out?

Well, yes, it is a diary. However, from what I can tell—and I’ve skimmed quite a few pages—it’s not so terribly private. There really just isn’t enough space on each page or each day for many private details, really. It is mostly a record of what happened each day. Very little space for reflection, or analysis, or introspection. So I don’t feel like I am invading his privacy, or at least in any way that he would worry about. But I do try to remember that it’s an artifact meant mostly for himself.

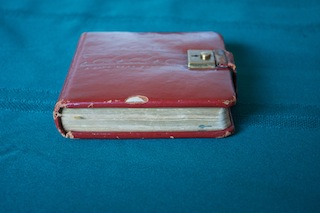

It’s a beautiful diary, though, and it’s amazing how well it’s held up over time. I give it a gentle pat each time I take it out of my computer bag.

I can’t believe how old it is. I started transcribing it almost exactly sixty years after he wrote it. There’s the thrill of the archive, the pleasure of research, that comes with transcription. It begins on his first day of boot camp. He was in the army for several years. As far as I can tell, it talks about his years in the military, including a brief stint overseas in Europe, and then about his return to the States and his first year or two of community college.

It says so much, and I have so much to say about it.

But for today I want to talk a bit about time travel. What I thought would be a linear journey through a five-year narrative has become something like an exercise in time travel, and it may be as close to tessering as I can come. My dad wrote this diary in the early 1950s, from early 1952-1956. The funny thing is that I also know how the story ends—I know where he ends up going to school, where his career winds up, and eventually when and how he meets my mother. Part of what I’m after in writing this book, though, is the story of the middles: what happened after he left camp, before he met my mother. So I’ll be reading, transcribing, and then some reference will come along (“so and so said that July 5th would be all right”)—and I can flip to that particular day, and find out what happened. And I’m also older than he was when he was writing the diary. It’s his early twenties, for the voice in the diary. It makes me feel oddly protective of the young man that he was.

But for today I want to talk a bit about time travel. What I thought would be a linear journey through a five-year narrative has become something like an exercise in time travel, and it may be as close to tessering as I can come. My dad wrote this diary in the early 1950s, from early 1952-1956. The funny thing is that I also know how the story ends—I know where he ends up going to school, where his career winds up, and eventually when and how he meets my mother. Part of what I’m after in writing this book, though, is the story of the middles: what happened after he left camp, before he met my mother. So I’ll be reading, transcribing, and then some reference will come along (“so and so said that July 5th would be all right”)—and I can flip to that particular day, and find out what happened. And I’m also older than he was when he was writing the diary. It’s his early twenties, for the voice in the diary. It makes me feel oddly protective of the young man that he was.

And at the same time, I am reading sooo slowly, much more slowly than I usually read. I read quickly (and then reread) often. So many of my books are books that I reread. But to read by writing each diary entry means that I am only reading as fast as I can type and then turn the pages. To read by writing makes me look, and look again. I’m not impatient with the work, somehow. I’m just luxuriating in this much time, and this much text: this much of my father’s voice.

One Reply to “This much of my father’s voice (The diary, part 2)”